Urge to Feel Safe

Anyone with an anxiety disorder will come up with various ways to feel safer. These are described variously as coping skills, compulsions, and rituals. We prefer the term safety behaviors because it describes the purpose of the action. Attempting to escape or finding a way to be safe is a biological demand in the face of real or perceived danger.

We are all ‘hardwired’ to respond instantly and intensely to danger. That happens in fractions of seconds before we can interpret whether the danger is real or not. That is a very reliable system and we are constantly fine-tuning it as we learn more and more about the world and ourselves. We are all trying to figure out what is dangerous and what is not. Although we are not always aware of it, this part of our nervous system impacts us continually, even during sleep.

Imperfect ‘System’

However, the system is imperfect and sometimes the result is excessive anxiety or an anxiety disorder. An anxiety disorder, among other things, is when the reaction is significantly incongruent with the actual danger according to one’s own view or that of objective observers.

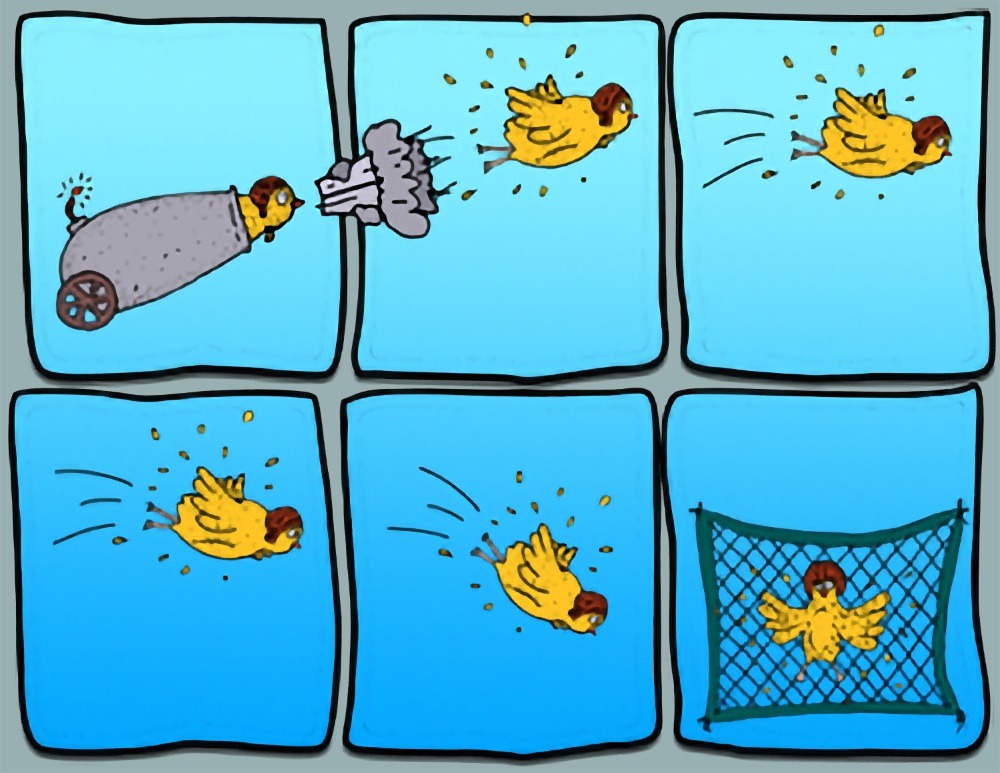

Part of how our normally reliable alarm system contributes to an anxiety disorder is the attempt to be safe. These attempts to be safer, paradoxically, end up perpetuating the excessive fear. When something is mistakenly viewed as catastrophic then the attempts to feel safe ‘confirm’ that something is dangerous and because it is avoided, experiences and information that would correct the mistaken belief don’t take place. Repetition reconfirms that something is dangerous as well as the belief that one is okay only because of the safety behaviors.

Increased Anxiety = Safety Behaviors

As emetophobia gains steam, children (and adults) create safety behaviors. Over time, these grow and become more elaborate. These are obeyed with great intensity. High anxiety is a complete authoritarian and demands obedience or an imagined catastrophe is predicted. If you haven’t had an anxiety disorder, it is hard to imagine the urgency and power it wields over someone’s life. If a child is pushed in a way that interferes with a safety behavior it will often lead to a meltdown of the first order. This is NOT evidence of bad character or oppositional behavior, it is terror.

Most safety behaviors from emetophobia are common to all, but we are ever amazed by the creativity of kids. As extreme or peculiar as some of these may seem to an observer, they are all just attempts to feel safe. Part of treatment is to persuade patients that giving these up will actually reduce the anxiety. However, just the opposite is the experience of someone with emetophobia. When they do things to feel safer, they will get some relief, at least at the beginning. The thought of stopping these is terrifying. Likely they have never stopped a safety behavior long enough to have the experience of the anxiety going down. Explaining how this works, starting the process of elimination slowly, and doing it gradually are crucial.

Examples of Safety Behavior

We provide an extensive symptom and safety behavior list located here and it can be downloaded and used freely. Below is a partial list of some of the common safety behaviors occurring in children. These are all specifically related to the fear of throwing up. If done for another reason, then don’t count it. For example, a child might be anxious about a cold but the actual fear is if the illness will lead to throwing up. Or a child may not want to go over to a friend’s house for dinner, not because of social or separation anxiety, but because something served could cause them to get nauseated and throw up.

Essentially, these are all ways of AVOIDING anything that might lead to throwing up. Generally speaking, these are not subtle behaviors.

Safety Behaviors for Kids/Teens

- Scanning for people who look like they might be sick or talk about being sick. If someone does get sick they might be avoided for a very long time, maybe indefinitely.

- Frequently scanning one’s body for any sign of illness (ex. Nausea, feeling in throat, fever, etc.)

- Asking for reassurance about whether one is sick currently or will get sick in the near future.

- Asking adult/parent to check body temperature (e.g., hand on forehead or thermometer).

- Checking on whether food is cooked enough, has been left out, or has expired. Avoid eating places where that information is not available (e.g., a friend’s house or restaurant).

- Avoiding anything that has been in contact with a sick person (e.g., desk, chair, school supplies, toys, etc.)

- Avoid sleeping alone in case they might get sick in the night.

- Avoid situations that might cause motion sickness (e.g., 3-D movie, travel, boats, roller coasters, swings, etc.)

- Avoid getting overheated.

- Avoid certain foods that could cause v***ting.

- Stop eating before feeling full.

- Eating very slowly or only in certain settings.

- Avoid being away from the safe adult(s).

- Worrying frequently about throwing up and planning ways to stay safe.

- Complains a lot about not feeling good (may be general but if asked specifically probably throat or stomach).

- Reactive or avoids references to throwing up in books, tv, movies, YouTube, TikTok, etc.

- Will avoid and may require others to not say anything related to throwing up.

- Excessive decontamination (or quarantine) of one’s body or items that may be contaminated with germs (e.g., excessive handwashing, cleaning devices, or showers).

- School refusal if there is a possibility of getting the stomach bug.

- Excessive use of things like gum, Tums, ginger, peppermint, or other medications to prevent getting sick or must have the available at all times.

- Performing superstitious behaviors (e.g., not wearing clothing associated with throwing up). Sometimes people use the word jinx. “If I do or don’t do ____ (whatever this might be) I will be jinxed and something bad will happen.”

- Doing subtle things like swallowing, pulling a shirt over the nose, mental neutralizing, etc.

Reducing Safety Behaviors

Just like facing challenges, in order to get over the phobia, these will need to be gradually reduced and eliminated. I usually start to work on these with kids after getting through a few of the steps so they have practiced getting anxious on purpose already. Sometimes the only way for someone to start exposures is if they can still use safety behaviors. It is okay to work on the exposure with a safety behavior first, then start to cut back on the safety behavior.

Here are some examples:

Safety Behavior: Asking adult if you are sick or going to get sick. (You are hoping they will tell you that you are okay.)

Challenge: If you ask 10 times, for example, try to only ask five, then four, then three, and so on. If you must ask, try to put it off for 10 minutes or longer.

Safety Behavior: Avoiding anyone or anything that may have come into contact with someone sick.

Challenge: Go places or near people you have been avoiding or go into a room you think might be unsafe. It could be a piece of furniture, clothing, or utensils. You can do it for a short time. If that is too hard, just walk near it or stand and look at it. When that gets tolerable then walk into the room or touch the scary thing.

Safety Behavior: Paying attention to how your stomach and/or throat feels a lot of the time.

Challenge: Practice letting your stomach feel uncomfortable and don’t do anything about it. You can give the feeling permission to be there. Think about it: it is already there, so why not change your response and see what happens. If you give it permission you are not responding like it is dangerous and, when you get good at that, the feeling will lessen.

Here is a link to an interesting audio recording by Dr. Claire Weekes. She is describing how to accept uncomfortable feelings rather than resisting them. This is quite a hard task and will take practice so don’t expect to be able to do this right away. In fact, you can just think about doing it at first if it seems to scary. (Note: This is a bit dated. For example, all the pronouns are masculine. However, the principle is always relevant.)

Safety Behavior: Checking food containers and packaging for expiration dates. Refusing to eat food if you are not 100% sure it is fresh.

Challenge: Check less often. And if you are pretty sure it’s good, don’t double-check it. If a parent says it is okay, take your chances.

Safety Behavior: Restricting the amount or type of food you eat. Many kids with this don’t want to feel full. Maybe certain foods seem like they could cause nausea, getting sick, or did in the past so you won’t eat them.

Challenge: When your anxiety wants you to stop, eat one more bite. Even if it is a tiny bite. Take a small bite of the foods you won’t eat. If that is too hard just look at it and think about taking a bite to start. Smell it. Work up to a bite. Then bigger bites after you practice.

Safety Behavior: Behaviors like coughing, swallowing, holding your breath, standing or sitting certain ways, not doing those things, or other body motions that make you feel safer.

Challenge: When you are anxious, do the opposite. If you tighten your muscles when you are worried, relax them instead. Sit instead of stand. If you are afraid to lay flat, lay flat. This will require you to notice other parts of your body when you are anxious. You probably are noticing your stomach or throat but switch your attention and see what else you notice.

Safety Behavior: Always listening and being on the lookout for anyone who might have or might get sick.

Challenge: Go around those places and people anyway. I don’t mean get coughed on by someone sick, I mean go by their desk at school for example. Ask an adult what they think is safe enough and go by that. Don’t leave the room or avoid the person after it is clear they are well. Unless there is very clear evidence someone is sick, act as if it is safe enough.